Sometimes in a garment or accessory, the main fabric needs to be modified in such a way to add stability, weight, or stiffness.

Usually, interfacing is tucked away in between multiple layers of fabric and you never know it’s there. Such as in collars, cuffs, and waistbands. However, without the power of interfacing, these garment bits will hang limp and not perform as they should.

What is interfacing?

Specialized fabric that is meant to add support or firmness to various pieces of a garment or accessory.

How specialized?

Very

Interfacing comes in two forms: Fusible and Non-Fusible (sew-in).

Suffice it to say, I rarely use sew-in or non-fusible interfacing.

In classic tailoring, there is a LOT of hand-sewn non-fusible interfacing. I’ve not done a lot of that.

Fusible Interfacing

Fusible interfacing comes in 3 types.

- Woven

- Non-Woven, and

- Tricot

Let’s start with tricot. It’s a knit fabric that is fairly lightweight. You might use this in undergarments or lingerie. Or delicate knit tops or dresses.

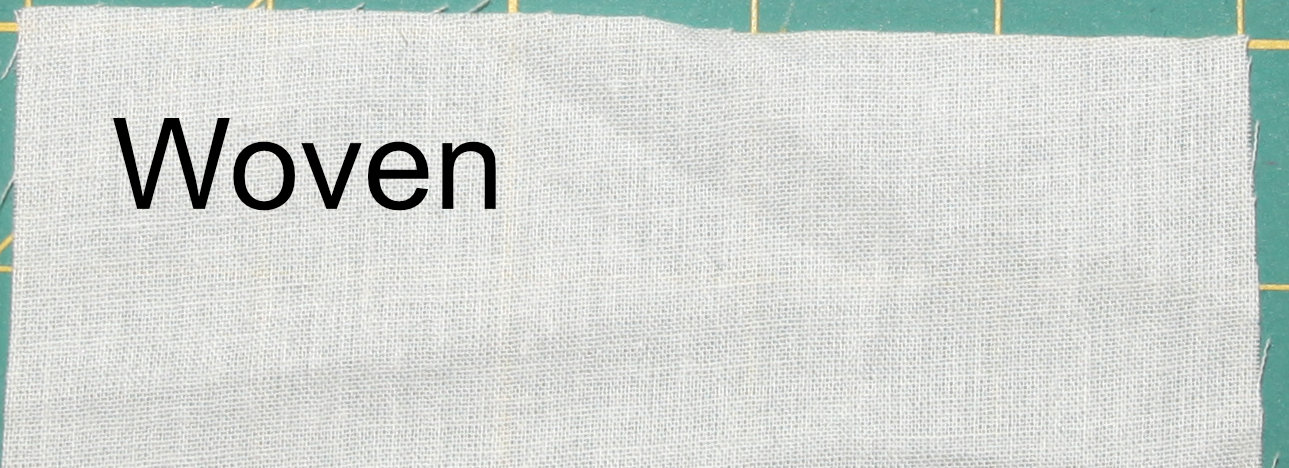

Woven interfacing is more commonly used for garments.

It’s woven like many fashion fabrics. And when applied, gives a firmness, without too much stiffness.

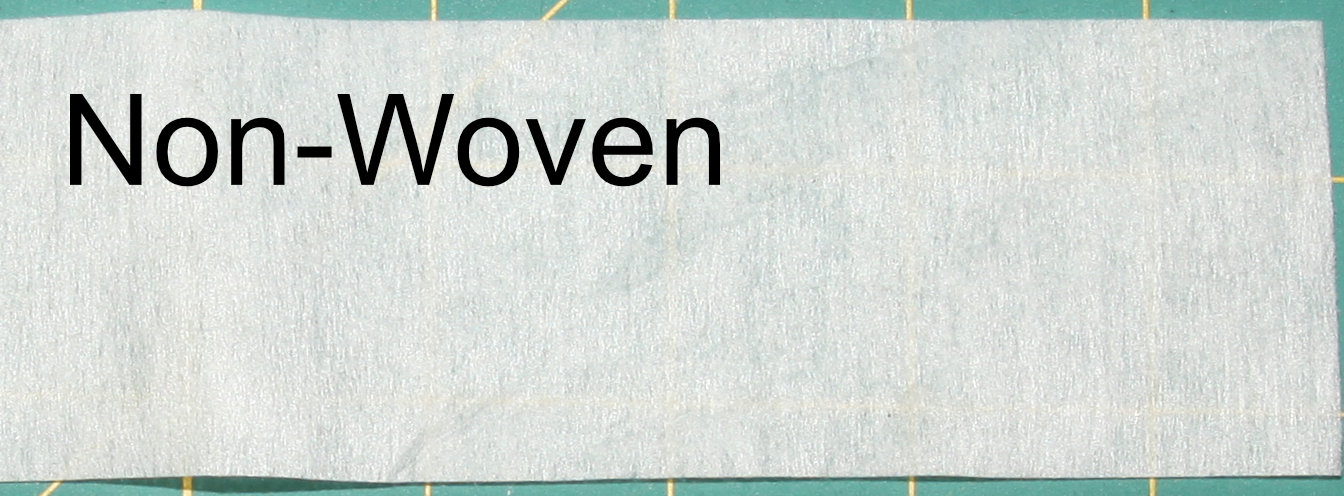

Non-woven interfacing isn’t woven. It looks like a thick paper that is made out of long fabric type fibers, rather than wood pulp. The fibers are matted together and go every which way. It adds a paper-like stiffness to the piece you interface with it.

Weight

Interfacing is usually classified (sized) by weight. It’s given the almost-useless designation of “Lightweight” or “Heavyweight”.

But, one brand’s “Lightweight” might be another brand’s “super-ultra-mega-lightweight”. 🙄

If you can feel it in a store, that could give you an idea of how they compare. If you’re stuck buying online, sometimes reviews can be helpful.

How to Choose?

Well, I’m going to assume you want the ease of application of fusible interfacing. So, we’ll start there.

Most likely, you’ll be choosing between non-woven and woven interfacing, so let’s forget about tricot.

One of the best ways to choose is to take some swatches of fabric and apply the different types of interfacing to it.

I used to use non-woven interfacing for everything.

Truthfully, I didn’t really know there was any alternative.

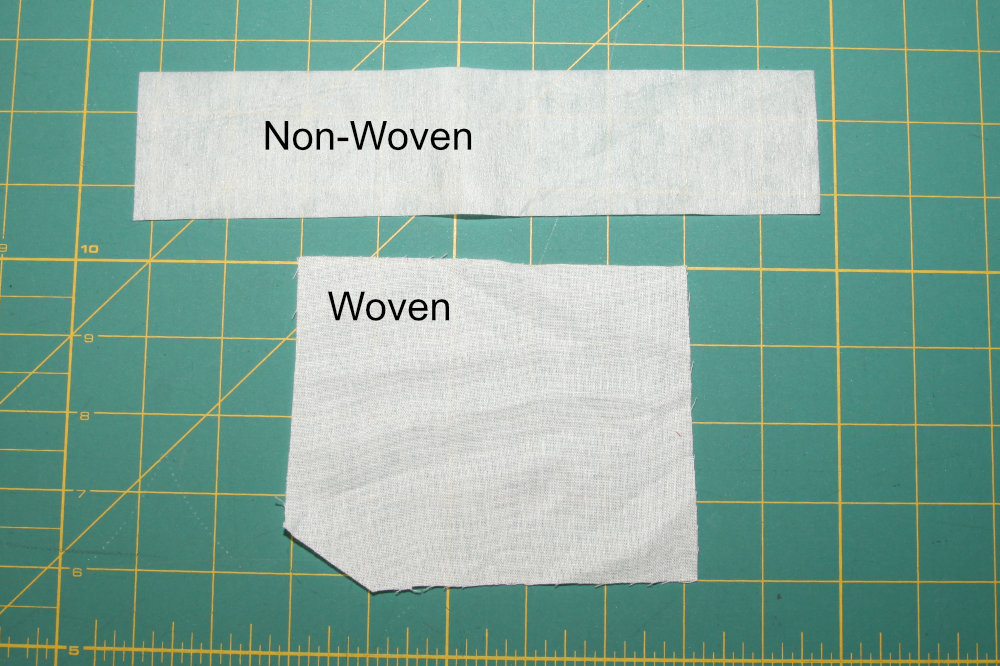

Non-Woven

Non-woven interfacing is very stiff. It doesn’t fray.

It’s great for stabilizing things that need a crisp firmness. Like fabric belts.

It’s also doesn’t stretch on the bias like woven interfacing (and fabric) does. So, if you need to stabilize something on the bias (like a contoured belt), a non-woven interfacing might be the right choice.

It doesn’t play as nice when having to be folded over and over. So, in the case of a bag strap or fabric belt that might be constructed by folding the strip of fabric in half lengthwise, I’d only use it on one half of the strip of fabric (minus the seam allowance) in order to reduce the bulk.

It also can get weird, kinda wrinkly, when you have to make something like a collar where you put two pieces right sides together to sew, but then have to turn it right-side-out and hide the seam allowance inside the burrito like thing. Frequently, you can press out most wrinkles. But it’s something to keep in mind.

Woven

Woven interfacing is much more fabric-like. So, you may opt for this in bag straps even.

It plays nicer when folded in half.

It does stretch on the bias. So, may not be the right choice to firm up something that you don’t want to have stretch, unless you put the stretchy bias part of the interfacing against the non-stretchy part of the fabric. Thats awfully complicated, and more than I generally want to think about when sewing.

In fact, most garment applications will likely be fine with woven interfacing. (Collars, cuffs, waistbands, button placards, pocket tops etc.)

However, if you need a much more stiff application (such as a high-standing vampire collar) you might want to try a non-woven.

Other Considerations

Lastly, the fabric you’re applying it to matters as well.

Stiff fabric with stiff interfacing will be REALLY stiff.

A super-light fabric might need a heavier or stiffer interfacing than a medium weight fabric, to achieve the same (desired) effect.

Both non-woven and woven interfacings are machine washable. Just make sure you enclose them in other fabric.

Over time, the non-woven will tear apart. And woven could fray.

Additionally, there’s a chemical in dryer sheets that can dissolve the “glue” that is used in many iron-on adhesive products So, if your interfacing isn’t snagged in the seam, and enclosed in the fabric, it could detach from the fabric and get really ugly.

I’ve seen it said that interfacing can shrink when washed (like fabric). But you can’t press it, and you can’t really pre-wash it.

I’ve also seen it said that you don’t need to pre-wash or pre-shrink your interfacing.

I don’t do it.

Sometimes I do shoot it with a bunch of steam before actually pressing it onto my fabric piece… just in case.

Your Informed Choice

I hope this helps clear up some questions on interfacing. For a lot of applications, there’s no real wrong choice, just better choices and worse choices. And in a lot of applications, it’s a personal preference.

Rather watch a video? Here’s one.